View Larger Map

Another exciting day on Route 66, with a huge load of things to write about. I drove in three states again today: Oklahoma, Texas and New Mexico. Texas, big though it is, has the second-shortest stretch of Route 66 among the eight states that the road passes through. Only Kansas has fewer miles. So I started my day in Clinton, Oklahoma, crossed Texas, and am staying for the night in the classic Route 66 town of Tucumcari, New Mexico.

The character of Route 66 shifted dramatically today. Today I really saw what a Route 66 ghost town looks like, and I saw it again and again in town after town. The rural towns and narrow, winding roads of the last four days have changed to towns that seemed to derive more of their business from Route 66 travelers, and straighter roads through completely empty flatlands. Demographics, climate, terrain, vegetation—big changes in all of them.

Breakfast in Clinton was interesting. I ate at a small restaurant attached to the motel where I’d spent the night. I overheard much chatter between a customer and the staff about local town folks—who was getting married to whom; who was whose uncle, aunt, son or daughter, and so on. A roofer talking about somebody’s son now serving in Iraq and his daughter looking for waitressing jobs.

After breakfast, I started my day with a visit to the Route 66 Museum in Clinton.

They have a good collection of material evoking the flavor of Route 66 over the decades, and lots of good information. My favorite exhibit was the late-1920s truck loaded up with supplies and baggage, just as it would have been during a real trip in those days. Notice the desert water bag, presumably for the radiator:

Remember that Route 66 crosses the Mojave Desert between Arizona and California, a stretch I will sadly not be doing on this trip.

After spending some time at the museum, I hit the road again, following Route 66 through the Oklahoma towns of Foss, Canute, Elk City, Sayre, Erick and Texola. I ran into a lot of trouble finding and staying with Route 66 in some of these parts. A word about navigating Route 66: this highway does not officially exist. In many places, it runs over complicated city streets. Numerous detailed maps have been published by enthusiasts to guide drivers, but it it still rather difficult to find all parts of this old route, especially without someone in the passenger seat to do the navigating.

In Canute, Erick and Texola I saw real ghost towns—towns that withered away after the interstate took away their traffic and livelihood. Starting here, the ghost towns have a very decrepit feel to them; there is invariably a lot of rusting metal as well as disused neon. In the 1950s, bright neon signs became hugely popular, and the many motels that had sprouted along Route 66 used neon signs to attract guests. A nighttime driver down a Route 66 town in those days would have been dazzled by the light display inviting him to stay at the roadside motels. Today, many of these neon signs remain; unlit, unclaimed and degenerating in neglect, the advertised business no longer in existence. Here are some I saw in Canute and Erick:

Texola is the last Oklahoma town before Texas. I’m not sure if I can call it a town. It has city limits and some street signs, but apparently no people, only yards full of rusting metal and rotting wood. The interstate runs just a short distance away, yet completely diverted the life out of this town. I would not want to be alone outside my car in Texola; even the brief period of time I had my window rolled down to take this picture gave me shivers, because there was some strange industrial sound emanating from this lifeless building:

With this ended my stay in Oklahoma, and I entered Texas. Route 66 cuts east-west through the northern projection of Texas, the Texas Panhandle. This was perhaps the flattest, lowest terrain of my drive so far. There were some trees initially, and in this wooded part I had a near collision with a rather idiotic deer. In Texas, the density of towns thinned down, and the towns themselves looked strangely desolate and eery.

I passed through Shamrock and McLean before hitting the freeway till Amarillo. A classic piece of Route 66 architecture is Shamrock’s very Art Deco U Drop Inn, a gas station and cafe dating back to 1936. It has recently been restored. In the old days it used to blaze with enough neon to glow over large distances across the Texas plains, and the restoration apparently has faithfully recreated that. In an act of defiance, I did not drop in, but only took pictures of the outside:

On the freeway drive to Amarillo, I took this drive-by picture of the famous leaning water tower in Groom, another Route 66 oddity-turned-roadside-attraction that drew travelers into town to spend their money:

In Amarillo, I ate at the Big Texan Steak Ranch restaurant, an institution among Route 66 travelers since 1960 (though now in a new location post-interstate invasion):

On the porch of the Big Texan Steak Ranch, I came across a flyer agitating for the use of English by Spanish-speaking Latinos, of which there are of course many in Texas. A reminder of the demographic variations I was driving through on this long trip.

Here’s the Big Texan gimmick: they will give away a free 72-ounce steak free to anyone, provided he or she can eat the whole damn slab of beef in one hour, along with sides of baked potato, shrimp cocktail, salad and buttered roll. (If the attempt fails, the customer pays.) In their own words, “Many have tried. Many have failed.” Well guess what—as soon as I settled into my seat, a challenger started working on his meal, and successfully ate everything in about 58 minutes, about as long as it took me to finish my sandwich and fries. I had timed my visit perfectly.

Outside of Amarillo is another legendary roadside attraction (popular with the Route 66 crowd now, but not originally linked to Route 66 itself): the Cadillac Ranch. I’ve been seeing pictures of it for years, and my curiosity has been slowly whetted over the years, so it was a great thrill to finally visit the place. It is best described by pictures:

This is a public art installation from 1974, commissioned by an eccentric millionaire, which is what I will be in my middle age. People freely spray-paint graffiti on these half-buried Cadillac chassis.

After Amarillo, I successfully stayed on Route 66 for the rest of Texas, passing through Bushland, Vega, Adrian and Glenrio. Ghost towns, all of them, especially Glenrio, with its chorus of dogs barking at me as I stood outside a house to take a picture. Adrian has a cafe, the Midpoint Cafe, claiming to be at the midpoint of Route 66 (between Chicago and Santa Monica). In reality, the midpoint of Route 66 cannot be defined.

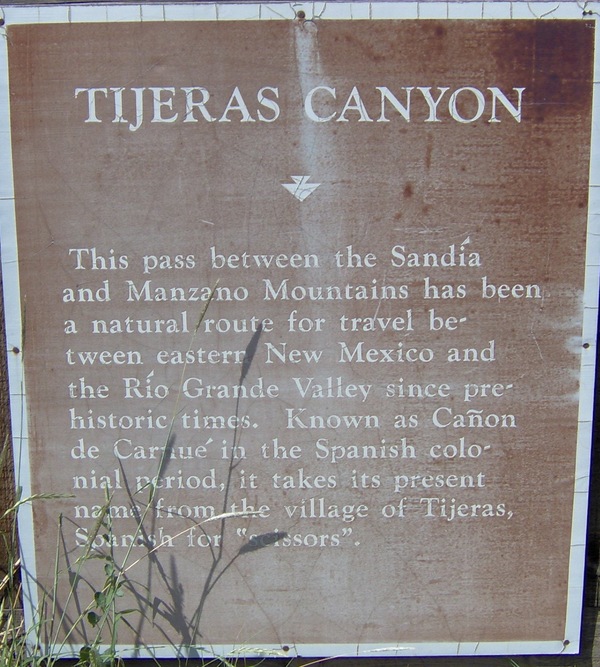

I left Texas and entered New Mexico, staying on Route 66 and headed for Tucumcari, where I intended to stay. The New Mexico terrain started displaying some distant highlands, unlike Texas. I will run into these mesas and buttes tomorrow, and in Monument Valley, but for today, the New Mexico landscape was just jaw-droppingly vast and open:

Imagine my disbelief when I came across a Punjabi dhaba at a gas station along Route 66 in the middle of this vast emptiness:

Outside of Los Angeles, this has to be the only Indian establishment along Route 66. I went inside and found quite a few Indian men wandering about, apart from the Punjabi proprietors. I tried to ask a couple of the customers where this hidden ore of Indianness was springing from. The first guy seemed suspicious of me and claimed he didn’t live locally (rubbish), and the second guy seemed uncomfortable with English and mumbled something in half-Punjabi, half-reluctance. I left this mystery unsolved.

Soon I reached Tucumcari. Tucumcari is classic Route 66. In the days of Route 66, a night’s stay at this town was customary among travelers. This tradition is still maintained by the revival travelers. Billboards along Route 66 used to be emblazoned with the slogan “Tucumcari Tonite!” to draw travelers into town for the night. Tucumcari has its share of abandoned businesses and non-functional neon signs, but unlike all the other small Route 66 towns I passed through today, Tucumcari still has managed to maintain a significant amount of the luster from the old days. Many of its neon signs still light up at night, failing motels have been revived under new owners, and many people do stay here for the night.

I was lucky enough to get the last remaining room at the historic and quite famous Blue Swallow Motel, a true Route 66 classic. It was built in 1939, and has recently been restored (but not ruined) by its new owners. They turned on their neon soon after I checked in. Classic stuff, and it feels great to be staying here.

I felt much less tired today, possibly it’s so much less humid in Texas and New Mexico than it was in the previous four states. Tomorrow, I drive across New Mexico.